From her bedroom door frame, Marjorie stared at Lucille. She’d covered her head with the quilt again. Brown ringlets, matching her own, strung out against the pillowcase. Shades drawn lights out, it could have been day or night. Though, Marjorie knew, among other things, that it was the day. Eleven o’clock to be exact.

“Lucille.” The floorboards creaked beneath the pressure of her feet. “Are you awake?”

“Not yet,” she croaked.

Marjorie let her finger wrap around the curl dusting her daughter’s earlobe. She’d had the ringlet since she was small. Even then, Marjorie could never stop herself from wrapping her finger around it, no matter how frail it felt now. A perfect ring, she would whisper. Luce would laugh as she understood.

“How are you feeling?”

“Tired.” Always, Marjorie thought.

“Maybe getting up might help.”

“Maybe.”

Luce’s voice was soft. Muffled by bedsheets and boredom. Marjorie attempted to remember a time when it hadn’t been, giving up when her memories felt more like film.

“Are you up for a diner trip?”

“I don’t know. Is it nice out?”

“Nice enough for winter in Maine.”

“Alright. Give me a minute.”

Marjorie nodded, unfurling her finger from Luce’s curl. Willing her lips shut, she counted the creaks on her way down the steps. Seven.

In the kitchen, John was brewing coffee. The whine of the kettle masked the puttering sound of their fridge on the fritz. His work boots on, she futilely attempted not to scrutinize the dirt smearing her tile floors. I’ll mop when he leaves, she consoled herself. Rubbing a slippered foot against her ankle, she stared at her husband’s slouched form.

Balding everywhere but by his beard, it was hard to remember what John had looked like when they were young. Fiery red hair, an eye for mischief, and a knack for convincing her to do just about anything were the most she could recall. Now, he carried lines where she used to feel freckles. Wearing a nearly permanent frown, he’d given away most of his smiles when he was too young to remember what they’d been for.

“How’s Lou feeling?”

Marjorie hated that nickname.

“Tired.”

“Hm.” He took a sip from his mug, handshaking, coffee sloshing on chapped skin.

“We’re going to the diner.”

He grunted.

“Do you want us to bring you back anything?”

His mug clattered into the sink.

“I’ll be on the docks by the time you get home.”

Instinct alone had her reaching for the soaped sponge. The sink sputtered alive, turning clear after a breath. Suds climbed up her arms.

“When will you be home?”

“If the weather is any good, five.”

“Alright. Anything you want for dinner?” Her question was met with a shrug and reddened eyes. Grabbing the dish towel from the hook above the sink, she dried out his mug.

“I better get going before the crabs start smelling up the garage.” He reached behind her, snagging an apple from the bowl she kept on their kitchen table. Three wooden chairs surrounded the circle. He kissed the space between her hairline and forehead, and she closed her eyes, preferring to hear his exit, rather than see it.

When the door clicked closed, she blinked. Her floors were a mess of footprints. In the coat closet, she found her mop.

~

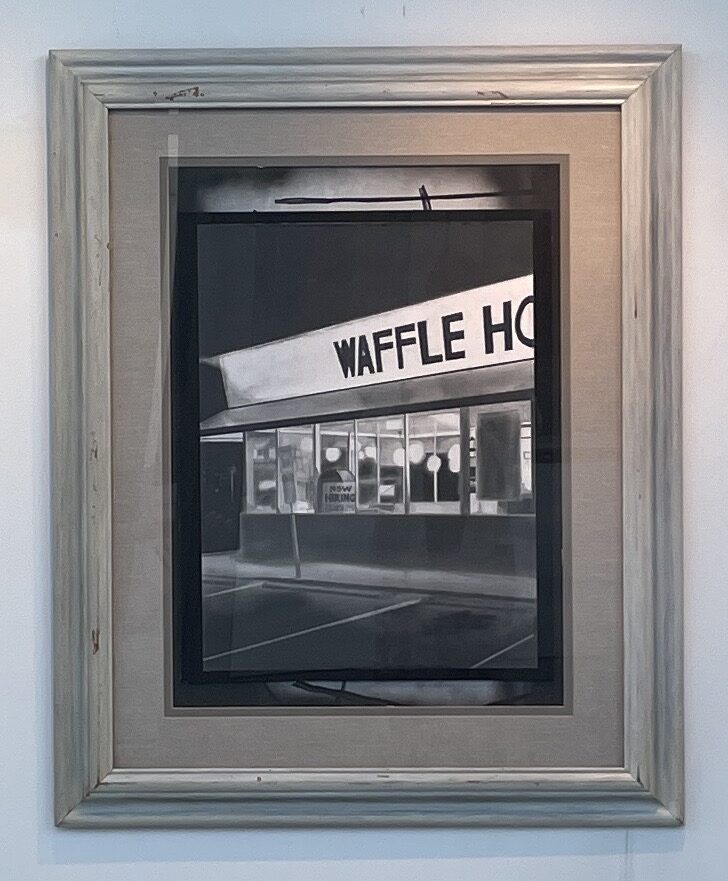

The diner was flush with fluorescents. It took a minute for her eyes to adjust. Across the table, her mother picked at a cuticle. This, for some reason, aggravated Lucille.

A dull chatter surrounded their silence. Luce picked up pieces of conversation, eyes wandering with her ears. An older man, around her father’s age, sat in a back booth, fingers clutched around a coffee cup. He swayed a bit, the drink holding him up. To his side, a woman, a bit older than Lucille herself, wrote something down in a notebook. Her shoulders were set straight, she looked like the tip of a ballpoint pen.

“What will we be having this morning, Greenes?” With grey roots and round cheeks, Ms. Grace had been working at the diner longer than Luce had been alive.

“A coffee for me is fine.”

“That all, hon?”

“Yeah.” She folded up the menu, taking care not to crease its edges. “Thank you.”

“Luce, you haven’t eaten anything all morning. Why not an omelet? Or pancakes?” Marjorie pointed her menu like a sword, cutting into Lucille’s swollen abdomen.

The click of a pen warned Luce of which side the old crone was on. Ready to scribble down her mother’s words, Luce found herself surrounded.

“Fine. I’ll have some pancakes, then.”

“And you, Marj?”

“An egg and cheese omelet is fine by me. Thanks, Gracie.” Marj gave one of her outside smiles, the one with teeth she saved for strangers on Sundays. “Oh, and one of those newspapers if you don’t mind.”

“Alrighty.”

With a wink directed towards Luce’s end of the booth, she left them for the old man, nose deep and eyes asleep in his drink.

Without their menus to use as shields or swords, Luce and Marj had nowhere to look but at one another. The dark shadows beneath her mother’s eyes had become perpetual residents. Hollow. That’s what Jude had said she looked like. Jude, whose own eyes filled her up, like her father’s whiskey bottles. Luce hadn’t disagreed.

“How are you feeling this morning, Lucille?”

“I’m alright.”

“Your joints?”

“Hurt.”

“And the headache?”

“Still there.”

They had a version of this conversation every morning. Luce could mouth the words that would come next. They’d settled under her skin, months ago, digging holes into her inflamed veins.

Marj extended her hand across the table, fingers picked raw. Luce placed her palm, wet with tap water, on top.

“I can’t wait for the day you tell me you feel better. To have my Luce back.”

She wanted to tell her mother that Luce hadn’t left. That she was sitting in front of her, bent over syrup stains, holding her hand. But, when Marj imagined the day she would get better, the day they’d find a name for what was wrong with her missing daughter, the shadows beneath her eyes lightened. Instead, Luce said, “Me too,” and the conversation ended like it always did. A tight-lipped smile and a scratch from a nail scabbed over meant to be soothing.

~

Moments later, Grace arrived with their food. She balanced their plates on the crook of her arm, holding Marj’s newspaper in one hand, and Luce’s coffee in the other.

“Maybe it’s the coffee,” Marj thought aloud. She had a terrible habit of doing that, especially around Lucille. Words often slipped.

“What do you mean?”

“Maybe cutting down on the coffee might help.”

“I already tried that, remember? It just made me more tired. And I told you to stop telling me what to eat.”

“I’m not. All I’m saying is maybe the coffee is part of the problem. You know diet plays a huge role in health.”

“I think I have a pretty good diet.” Luce turned her shoulder, taking a sip from her mug.

“I never said you didn’t.”

“I feel like it was implied.”

Marj opened the newspaper. Crinkled pages muddled with empty words. Her eyes glossed over the spaces filled with cartoons. John’s favorite section. He’d probably already read them all that morning, but she’d stuff the pages in her purse for later just in case.

The international section talked about a story in China. Cases of pneumonia had broken out and possibly another virus. A new one. It’s because they live on top of one another, Marj thought. Just like in New York.

“You see this?” Marj flipped the paper around. Crumbs from her breakfast found homes within the ink.

“What am I supposed to be looking at here?”

“International. See all those cases of pneumonia. A new virus they think.”

“So? That’s all the way in China, Mom.”

“It can happen anywhere, Lucille. Especially in crowded places like New York City.” She folded the paper up, stuffing John’s pages in her bag. “Could you imagine catching that on top of whatever this is?”

Luce bit back a laugh.

“What?” Marj stabbed her fork into an egg.

“I know you don’t want me going to college in New York, but that was a bit of a stretch, don’t you think?”

“I just worry for you. Especially now with this sickness. You don’t take your health seriously enough.”

“Yes, I do.” Luce was playing with the button of her coat. A button Marj had stitched back on more times than she could count.

“You could go local. Even if Jude ends up in New York, she’d come back to Maine for the holidays. And summers.” The button’s yarn began to uncoil.

“I don’t want to go to New York just because Jude is going there.” Strings dusted her wrists.

“You and Jude are in two different situations. You can’t base every decision off her.”

“I’m not.” Strands knotted, held together by nothing, but one another.

“Yes, you are. You can do your writing from home. Save money. Search for a doctor.”

“New York is only a few hours away. The schools are better. So are the doctors.”

“I get it.” Marj clutched her drink, peering out the window. “Anywhere is better than here.”

The button popped.

“I never said that.”

Marj nodded, holding her head and hair together with the palm of her hand. Luce reached over their food, taking care not to disturb their clutter. Her cup had already made a ring around the news section. Luce rubbed a soft finger against the flannel of her mother’s shoulder. Marj leaned into her daughter’s touch.

“I know. I know New York has more opportunities,” she murmured into the stuffy air. “I’m sorry. I’m just… worried.”

“I know.” Her voice had lost its edge. Something it didn’t often do. “Who knows where I’ll end up, you know.”

“Give me that button. I’ll stitch it back on before you go out tonight. You need to wear your coat.” Luce rubbed the plastic against the pale skin of her finger. Marj peeled the button from her palm, a mother again. “Let’s grab the check.”

~

The outline of the lighthouse was the only thing she could see when Jude pulled up. Her car was what Luce’s father called a death trap, but it was a moving death trap. So, when they skidded to a halt as gravel turned to swamp, Luce just blinked.

“I wore the wrong coat for this shit.” Jude’s voice was muffled beneath the engine’s spit. She was right, though, about the coat.

“Well, we made it this far, haven’t we?”

“Yeah, yeah. And we remembered the important stuff.” She knocked Luce’s elbow, gesturing towards the grocery bags, her mother tended to knot and hoard.

Outside, the wind was bitter. It bit at their cheeks. Luce found a pair of gloves in her coat pocket. A leftover from last time.

“Was this a stupid plan?” The air made Luce’s words sound disjointed and cold.

“I’d prefer if we called it an adventure.”

Luce laughed.

Slush from last week’s storm found its way into her boots, wetting wool socks. Jude was knee-deep, her pantlegs soaked to the bone. Flurries dusted their scalps, quiet signs of turning back. The ocean roared around them.

The lighthouse grew closer. From where they stood on the cliff, Luce spotted the small cottage to its side. When they were young and sometimes still when they were drunk, they’d make up stories about the old man who lived there. Or at least they’d assumed he was old, a man, and very much alone.

At the water’s feet, they laid out a blanket. Luce sat first, her joints groaning for rest. The bag lay next to her. And they both watched as Jude ran to the cliff’s very edge, leaning over as if she were ready to jump.

“I really am not in the mood to hide a body tonight, Jude,” Luce shouted above the wind.

“I’m offended you wouldn’t choose an open-casket funeral.”

“I could never tell anyone. They’d frame me for murder.”

“Well, murder suspect or not, I’d come back as a ghost and haunt you.” She lifted her arms up. A zombie.

“I’d be offended if you didn’t.”

But she stepped away from the ledge, creeping back to where Luce sat on the blanket. Hands slick with sweat and numb with ice, Luce struggled to unknot the bag.

“You always tie this thing so damn tight.” Jude grabbed the bag, doing the rest of Luce’s work with the ease of a sailor. Unscrewing the cap, she inhaled the intoxicating scent of whiskey. “You sure he won’t notice?”

“He never has, right?”

Jude shrugged, tipping her head back with the bottle. Pinching her lips tight, she passed it on to Luce. And they repeated this pattern until their hair was white with snow, their bodies light with liquor.

“So, the man in the lighthouse?” Jude was playing with Luce’s curls. Her finger found the ring Marjorie loved.

“Yeah?”

“Tell me his story,” she hiccupped. “You’re good at those.”

“Alright. Well, you know he had a wife once. And a cat. They never really got to the child part. He was okay with that, though. His father was a deadbeat himself.” She pointed to the bottle. “They’d bought the lighthouse in the summertime. You know how Maine’s summers can trick you. The sun’s there, and you think to yourself, well this is sweet; winter can’t be all that bad. But it always is. Their first winter, she stayed. Weathered the storms. She had all these wonderful memories of summer locked inside her head. When things got hard, she’d let one loose, and think to herself, see this is why I stay. And soon enough, summer came. And it was just as sweet as she remembered. Just as sunny. Just as short. The second winter was harsh. She was starting to question the storms. One night, after a bad one, she told her husband, we’ve got to move. He didn’t understand. To him, the winters weren’t too bad. He was used to them. He’d lived in Maine all his life and didn’t know much else. But she did. She knew what it was like to live without storms. And she told him about it, except by then it was too late. He’d gotten used to the weather. So, she left. Took their cat too. And that’s how he came to be alone.”

Snow enveloped their breaths.

“He should’ve gone with her.”

“Yeah, he should’ve.”

Jude reached for Luce’s mittened hand, swallowing back a chill. She stared at Luce, choking her with her eyes. “Have you thought more about New York?”

“Yeah.” Luce squeezed her hand between their fabrics. “I want to go.”

“But?” Jude murmured, trailing her fingers underneath Luce’s layers.

“I don’t know.” She picked at her button. “I think I’m a little lost.” She peered at the sky. “You know the mirror in my bathroom? The one with all those spiderweb cracks?”

Jude began outlining the freckles on Luce’s stomach, tracing her lungs.

“In the morning, when I’m getting ready, I’ll just look in that mirror and it’s like every day I see someone different. Sometimes, I’ll wake up and all the swelling is gone from my face, and I’ll stare at myself and touch my jaw and think I’m back to who I used to be. But then I’ll run my hands through my hair and clumps will fall to the floor and I’ll look at myself again and see that actually my left cheek is bigger than my right and my wrists are huge and I’m not at all who I used to be.” She sucked in a rattling breath, shaking Jude’s hands. “And then I’ll think about how no one, not even me, knows what the hell is the matter and it’s like I’m chasing this person, we’re all chasing this person, who doesn’t exist anymore.”

Pulling up her coat’s collar, Luce wiped her nose. The air fell still and so did Jude, neither rushing to grab her confession.

“I think you’ll be that person again. We’ll figure out what’s wrong. And get you fixed. And then we’ll move to New York. And live in a tiny studio apartment. And every morning I’ll wake you up with a cup of coffee and we’ll stare into that stupid cracked mirror together and some days we’ll know exactly who we are and some days we won’t.”

And what about after that, thought Luce. When you get tired of chipped coffee cups and cracked mirrors. When you meet a boy whose legs stretch two subway seats long and decide you like the steady rhythm of his heart better than the skip of mine?

Jude’s fingers crawled further up to her sternum. “Eventually, we’ll be alright,” she breathed, watching the nod of Luce’s head, hugging the winter beat of her heart.

After that, they were quiet for a while. And then they weren’t. And then it was midnight, and the bottle was empty, so they turned to one another.

“Happy New Year, Jude.”

“Happy New Year, Lou.”

Jude kissed her cheek. They traded coats. And went home[BKM1].

~

“What happened to your coat?” Marj had been waiting at the kitchen table, elbow propped up on yesterday morning’s paper.

The curtains were drawn, except for the sliver she used to spy. John’s snores echoed through hollow walls.

“I lent it to Jude.” Bulbs flickered above their heads. “Dad needs to change the lights.”

“He’s been busy at the docks. It’s crab season.” The lie stuck to Marjorie’s gums like refrigerator magnets.

“Alright, I can fix them in the morning.” She’d found her way to the railing. The rest of her life was still a bit blurry, which always made her mother’s words cut sharper.

“Why did you give Jude your jacket? I just fixed that button.”

“She didn’t bring the right coat and she was cold. I’ll get it back tomorrow.” Luce was one stair up.

“And what about you?”

“What about me?”

They were halfway to the second floor. Unsaid words hung from the banister.

“You weren’t cold?” Marjorie whispered.

“I wore it for most of the night.”

The snoring stopped.

“You care more for her than you care for yourself.”

Sheets ruffled. Hard feet fell to the floor.

“Isn’t that what love is?”

“God dammit, Marj. I’m trying to sleep in here.”

Marjorie thought the dark hid the bulge of her irises, but it never did. Neither did her cleaning hide the rage that covered their house in a fine layer of dust.

“Come sleep in my room tonight.” Luce was whispering now.

“Why?”

You know why, she thought.

“I’m not feeling well,” she said instead.

“Oh.” Marj pressed her lips to Luce’s forehead, checking for a fever they both knew wasn’t there. They tiptoed to her bedroom, hand in hand. When their heads fell to the pillows, Marj wrapped a finger around Luce’s ring, frail herself.

Luce lay awake. Her mother’s uneven breaths in her ear, she listened to the sounds the house made to fill these kinds of silences.